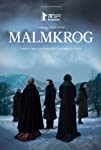

Eye For Film >> Movies >> Malmkrog (2020) Film Review

Malmkrog

Reviewed by: Anne-Katrin Titze

When “the devil’s tail scatters fog across the created world”, a gauzy kind of disquiet settles in. Of course, the exhaustion of Earth is a sign of the anti-Christ. Cristi Puiu’s Malmkrog, which had its world premiere at the Berlin Film Festival, and is now having virtual screenings at the New York Film Festival as a Main Slate selection, takes us to the Transylvanian village that used to bear the name of the title during the Austro-Hungarian empire. The 20th century is about to begin. Based on Vladimir Solovyov’s philosophical novel War, Progress, and the End of History: Three Conversations, Including a Short Story of the Anti-Christ, Puiu’s film, divided into six chapters named after the six protagonists, takes place in the elegant Apafi Mansion, a house with a long history of confiscation, nationalisation, and restoration. Without knowing any of this, you can sense its history - our past, and the future for the characters within the film.

A snowy landscape, church bells, a woodpecker heard doing its job. A child is being called to come inside the powdery-pink estate. A black dog plays with a stick, a shepherd with his flock comes through. The child could be us, the audience, summoned by the sophisticated, beautifully dressed (costume design by Oana Paunescu) late 19th century adults who will talk up a storm of good and evil, war and peace, Christ and anti-Christ for the next three plus hours. We don’t know exactly who these five eloquently talking people are, nor how they are related to each other, while they have elaborate meals (which they take for granted), while being doted on by servants (whom they take for granted as well). The refined dinner table is - as though Puiu had a premonition - set in a socially distanced fashion, matching the stubbornly unmovable opinions of the guests.

What they say, mostly in French, with short excursions into German or Russian, is wildly fascinating and there is more substance of thought in one minute of this film than most movies are able to produce in an hour. Seeing and listening to Solovyov’s contemplations this way is a challenge (comparable to Bruno Dumont’s take on Charles Péguy for his Joan of Arc films), but the actors do one hell of a job in their delivery.

The six chapters, which are named after the host, Nikolai (Frédéric Schulz-Richard), his four guests, Olga (Marina Palii), Ingrida (Diana Sakalauskaité), Madeleine (Agathe Bosch), and Edouard (Ugo Broussot), plus Nikolai's critical head butler István (István Téglás), follow a deceptive chronology, just enough askew to make you wonder. Virginia Woolf readers know how to identify the passing seasons by the types of flowers on the table. Malmkrog has a Christmas tree as a misleading pointer, or maybe not. Linear time is not of interest here, nor, despite the setting, are Chekhovian entanglements and mind games.

The debates, continuing relentlessly, from one room to the next, during meals and tea and short breaks in the salon or on the porch, are all staged in constrained visual perfection (cinematography by Tudor Vladimir Panduru of Cristian Mungiu’s Graduation). The arguments are paramount, their subject matter the opposite of a MacGuffin, as they expose the speakers’ belief systems, their colonialism, upbringing, faith, or aplomb.

Of all the films I have seen so far in this year’s New York Film Festival, besides the heart-rending, high-priority Gunda, Malmkrog is the most haunting, the most thrilling, even days later. It is the combination of the ornate compositions of shots with the expert delivery of concepts that very much still resonate with us today, and the excellent actors, whose faces make you understand their positions - all of it together pushes cinema forward. The famous William Faulkner quote is again painfully adequate - “The past is never dead. It's not even past.”

There is Ingrida, wife of a colonel and count, who lies sickly in another room of the mansion. She has a Bergman aura in her stately dress, which is the colour of dried blood. She relays to the group a letter from her husband who witnessed a massacre and is convinced that war is sacred. There are only two kinds of saints, she points out, monks or princes, who were soldiers.

Madeleine, whose name we find out last, is a pianist, dressed in black, and the only one to come to the defence of Olga, who is the youngest of the group, a devout believer in goodness and the power of consciousness. Edouard, a politician who loves to gamble in Monte Carlo, explains his colonialist ideas. “Absolute rules were invented by those devoid of any sense of reality,” he says and believes that Russia’s position is that of a buffer between the West and Asia, to “keep Europe out of war” and to “civilise the Chinese.”

The host Nikolai, a former seminarist, in response quotes Goethe’s Faust back to Edouard (“Zwei Seelen wohnen, ach! in meiner Brust.” - Two souls alas! Are dwelling in my breast), giving the line new context, but also introducing the devil, his own pet subject. Frédéric Schulz-Richard gives an exceptionally imposing performance, reminding us that “the master demanding good does not necessarily mean the master is good.” Nikolai, bible in hand, verbally duels with Olga, and corners her into the argument of “Christ not being imbued with enough Christian spirit.”

Puiu changed the genders of some of Solovyov’s characters - to great payoff. The women are holding their own in the debates, something many period pieces have a harder time showing. There is a moment in the film that altogether startles the house and us. The sequence is introduced by mysterious sounds coming from god knows where. Has the child from the start grown up to become a silent-movie accompanist? The non-consequence of what happens next can only be understood by taking into account one of the topics discussed: Resurrection.

Is not cinema the art of resurrection? You don’t even have to be literal, as with Carl Theodor Dreyer’s Ordet, Veit Harlan’s Opfergang, or Alice Rohrwacher’s wondrous Happy As Lazzaro (Puiu’s own Mr. Lazarescu in the Death Of Mr. Lazarescu doesn’t have the name by coincidence).

Audiences have to stay on the ball, thinking back in time as well as forward while these well-mannered, well-dressed privileged women and men talk of a future European Union, a Kingdom of Heaven and a Kingdom of Death, good peace and bad peace, stages of moral development, intellect and conscience and how “like waterlilies when you pick them you sink in the mire.”

Malmkrog makes you suddenly aware that the possibilities of “talking pictures” have not yet been totally investigated.

Reviewed on: 19 Sep 2020